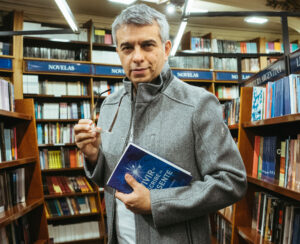

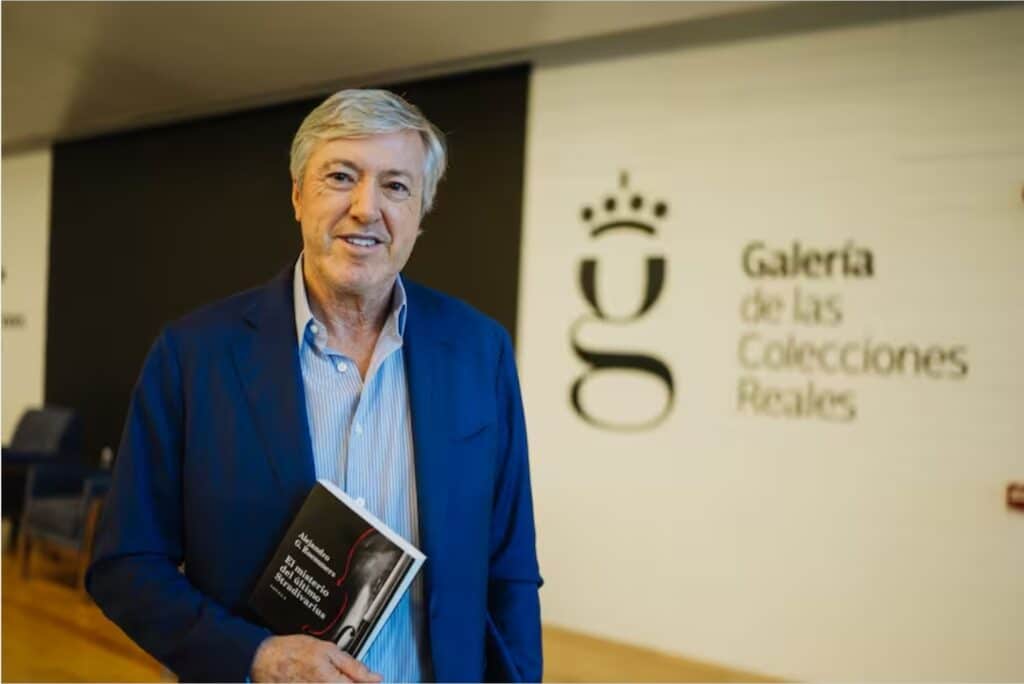

More than 200 cultural figures attended the presentation of the latest book by the Argentine writer and poet at the Gallery of the Royal Collections in the Spanish capital.

MADRID — The Gallery of the Royal Collections is surrounded by the gardens of Campo del Moro and watched over by the Almudena Cathedral and the Royal Palace of Madrid. In its main hall, more than 200 prominent figures from the worlds of literature, art, and Spanish société gathered for the presentation of The Mystery of the Last Stradivarius, the latest novel by Alejandro G. Roemmers. The book had already premiered earlier this year at the Buenos Aires Book Fair and in the city of Cremona, Italy, and features a prologue written by Mario Vargas Llosa shortly before his death.

Among those in attendance were Manuela Villa Acosta, General Director of Cultural Affairs at the Office of the Spanish Prime Minister; Cecilia Meirovich, Cultural Attaché of the Argentine Embassy; David Donaire, Deputy Director of Cultural Affairs at the Office of the Spanish Prime Minister; Mariano Jabonero, Secretary General of the Organization of Ibero-American States for Education, Science and Culture (OEI); Ana Botella, former mayor of Madrid and wife of José María Aznar; and Telma Ortiz, sister of Queen Letizia and advisor at CEAPI.

Next to the author sat two acclaimed Spanish writers: María Dueñas (The Heart Has Its Reasons, The Seamstress, The Captain’s Daughters, among others) and Carmen Posadas (Little Indiscretions, The Legend of the Pilgrim, License to Spy). In addition, Raúl Tola, director of the Vargas Llosa Chair, led a warm conversation that intertwined aspects of the book’s creative process, Roemmers’ close friendship with Pope Francis, and the bond he maintained with Vargas Llosa for more than a decade. In the background, a stunning view of the city completed the scene.

“I feel deeply moved, because I would have loved for Mario to be here at the presentation of the novel and to read the prologue himself. But well, he made sure that his son Álvaro would do so at the Buenos Aires Book Fair,” Roemmers began.

The novel is structured as a mix between historical narrative and detective thriller. The story traces the journey of the last violin crafted by the legendary luthier Antonio Stradivari over three centuries, during which it becomes a silent witness to major events in world history—until it ends up in a small town in Paraguay, inside the home of an art collector murdered along with his daughter under mysterious circumstances.

That crime, which took place in 2020, sparked Roemmers’ curiosity and served as inspiration for weaving a plot that connects Stradivari himself, Verdi, and even a Nazi officer as possible owners of the treasured instrument.

“I must confess I felt quite envious that you came across this story. For those of us who specialize in historical novels, this kind of real-life mystery is extremely appealing. I have no doubt that Vargas Llosa, who was a great hunter of stories, would have been fascinated as well,” said Posadas.

“I read about it on my phone during the pandemic, which I spent on a ranch we have in Córdoba, and I found it very strange that such valuable instruments appeared there without anyone knowing how they had arrived in that town,” recalls Roemmers. “That was the thread from which I began to build an entire story involving the treasures the Nazis had seized from concentration camps. I also discovered that in those horrific places there were many prisoners who played instruments. So, when I began writing the novel, I also thought about the mission of music: to keep the human being, human. It’s what still protects us today, as the last frontier against dehumanization.”

However, the initial focus of The Mystery of the Last Stradivarius appeared in Roemmers’ imagination in a different way: “I originally thought of writing about two violins, and the title was going to be The Cursed Violins, because they brought bad luck. I wrote several chapters with that idea, but later I felt I didn’t want to associate music or art with anything negative. So, I decided to leave that plot behind, although all the research I had done on Cremona and also on Paraguay helped me build the story. I then chose to focus on a single violin—not a magical one, but one with a very special sound, in which Antonio Stradivari had put the best of his art, capable of deeply moving anyone who listened to it. I think that’s the great virtue of art—and especially of music—that it can move us, make us tear up, and soften our hearts.”

María Dueñas highlighted Roemmers’ way of telling the story and how he built a plot on two levels, intertwining the historical and detective narratives: “Those of us who dedicate ourselves to storytelling always ask questions that go beyond the plot itself and deal with the structure of a novel. What was the challenge of building two such different layers, giving them coherence, balance, and credibility, so that the novel ultimately feels unified? In your book, two intrigues unfold in parallel, and both maintain a high level of interest without ever clashing. On the contrary—they enhance one another, and by alternating, make the reading experience even more engaging.”

“In the European part of the story, I focused especially on achieving the most accurate setting possible, even including real historical figures of the time,” explains Roemmers. “Authentic historical characters coexist with fictional ones, and I like to leave a veil of mystery over which are which, so that curious readers can investigate for themselves. The idea was to weave them together so seamlessly that the difference wouldn’t be noticeable. The hardest part was ensuring that the present-day investigation in Paraguay could balance the richness of the European section. That was a true challenge.”

Of Nazis and antiheroes

One of the central characters in The Mystery of the Last Stradivarius is Commissioner Tobosa, a Paraguayan police officer obsessed with the murder of the luthier and his daughter—and with the mysterious instrument itself. He’s a kind of anonymous hero full of good intentions, accompanied by Gutiérrez, a dim-witted but ambitious officer.

“Both have something of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza in them, but with a key difference: the assistant isn’t loyal, as is usually the case in such duos—quite the opposite. I wanted him to represent those people who perform humble, silent tasks, and whom we only recognize as heroic when something extraordinary happens,” Roemmers explains. He adds: “I was thinking of figures like police officers, firefighters, nurses, or doctors—professions often undervalued, with low salaries and great sacrifices, whom we only appreciate when they save us in an emergency. That’s the spirit I wanted to convey in the character of the commissioner: someone life seems to punish, struggling in work and in love, yet who still preserves his kindness. That combination of fragility, decency, and humanity is what gives depth to the character.”

“Another of the key characters is the Nazi officer,” adds Posadas. “He’s the head of a concentration camp in Trieste, Italy, where one of the prisoners is an extraordinary violinist whom he forces to play music that, in a way, masks all the horror taking place. It’s what Hannah Arendt called the banality of evil. This man, who may once have been a good son, becomes a monster, but at the same time, through the music of that violin, somehow reconnects with the best part of himself.”

“Yes, I wanted to show that ambivalence,” Roemmers agrees, “because I’ve often discussed whether a great artistic creator must necessarily be a good person. In my idealism I assumed yes, but I was quickly proven wrong,” he confesses. “Curiously, what I tell in the book has points in common with two real-life events reported recently: the discovery in Argentina of a painting by the Italian Giuseppe Ghislandi, seized from an art collector during World War II, and the finding in Japan of a stolen Mendelssohn violin. It’s as if this story remains alive, still writing new chapters to the novel.”

In the novel’s dedication, Roemmers includes his mother, some friends, and Pope Francis, with whom he maintained a friendship both when he was a cardinal and during his papacy. “We spoke often about what we could do for peace, and he invited me to join his Fratelli Tutti Foundation, inspired by his encyclical on universal fraternity. There, I chaired the Literature and Fraternity roundtable at the Vatican, in addition to organizing a soccer match for peace at Rome’s Olympic Stadium and a symbolic embrace among young people from around the world—first in Assisi and then in Rome—with 180 youths, 30 Nobel Prize laureates, and artists like Andrea Bocelli. Francis couldn’t attend because of surgery, but he watched it on television and told me, ‘I saw you, you did very well.’”