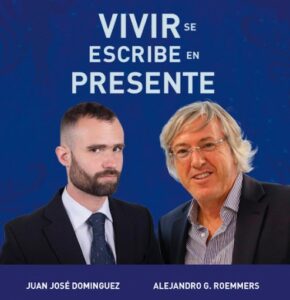

The businessman and writer and the eldest son of the Nobel Prize winner reflect on their years of friendship and the legacy they have received.

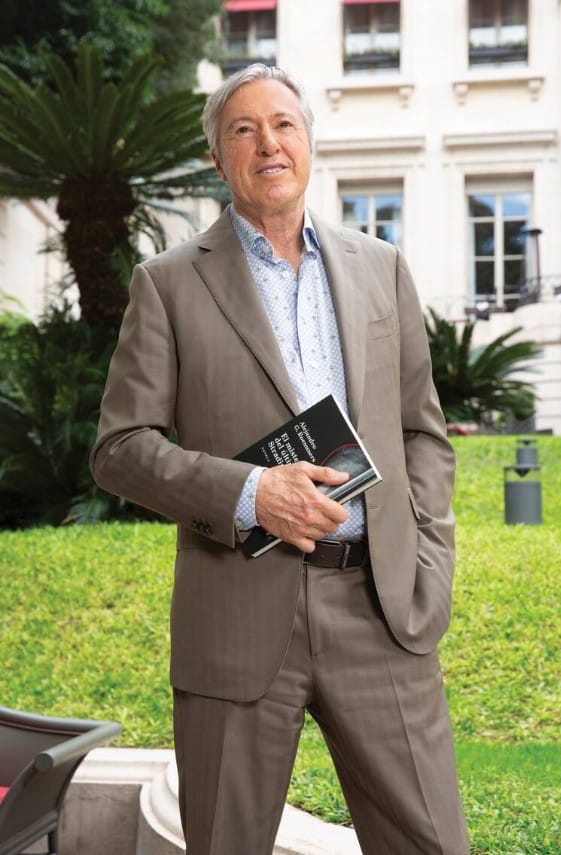

The embrace they share upon seeing each other says it all: a heartfelt conversation between two friends who admire and respect each other so deeply that not even the deepest sorrow could break a promise. ‘I had given my word to Alejandro, whom I deeply appreciate. These are not the happiest circumstances for me, but here I am,’ says Álvaro Vargas Llosa (59), just days after bidding farewell to his father, Nobel Prize-winning author Mario Vargas Llosa (who passed away on April 13). Beside him, businessman and writer Alejandro Roemmers (67), who invited him to participate in the presentation of his latest novel, The Mystery of the Last Stradivarius, at the 49th Buenos Aires International Book Fair, appears moved and grateful.

–How did you two meet?

Álvaro: Through a mutual friend, Gerardo Bongiovanni, several years ago, right here at this hotel (Palacio Duhau Park Hyatt Buenos Aires). Alejandro has also been a valuable contributor to a foundation my father chaired, the International Foundation for Liberty, in which I’m deeply involved. He’s a friend with whom I’ve had many conversations, especially about literature—talks that have taken place in various countries, mainly in Spain, where we’ve met most often. I admire his passion for literature, I appreciate his work and his sensitivity toward the literature of others, including that of my father. I know he held great affection and literary admiration for him.

Alejandro: Mario Vargas Llosa’s fight for human freedom in every sense resonates deeply with me because I have a spiritual vocation. It moves me that he wanted to write the prologue to my latest novel. And the way he did it—he focused entirely on me as a person.

Álvaro: I used to talk about that with my father. If you meet Alejandro without knowing his background in business, your first impression is that he’s a dreamer, with his head in the clouds—someone you’d never expect to function effectively in the tough world of business. But his personality is fascinatingly complex. He can create poetry, imagine a world like the one in this novel that spans broad historical periods, and at the same time, he’s very grounded—capable of multiplying the value of a company (Roemmers Laboratories, founded by his grandfather). That’s something very few people can do.

–The title of the novel refers to music. What role does it play in your lives?

Álvaro: When I was 14, I joined the Orpheus Society at school. A group of us would meet on Saturdays to listen to music, mostly classical, and then give a short presentation on a musical piece or composer. For many years now, I’ve attended the Salzburg Festival every year—my father went for 33 consecutive years. In these past few months, when his health deteriorated significantly, music was one of the things that kept him going. When he could no longer read, he could still listen to music, and playing a two-hour concert for him made him incredibly happy. The doctors told us: “The last thing to go at the very end is the ear’s sensitivity to music. Even if he can’t respond or communicate, he’s still listening.” When he was on his deathbed, almost at the threshold of death, we played Mahler for him, and it was moving to know that, deep down, there was still a Mario Vargas Llosa reacting to sound.

Alejandro: I had a similar experience with my father (Alberto Roemmers). He left written instructions that after his burial, a celebration was to be held at the Alvear Hotel, and he planned everything—food, wine, and the music: Viennese waltzes.

–You both had strong-willed, successful fathers. What memory brings a smile to your face?

Álvaro: When I think of my father, I don’t think of the public figure. It’s the private man who comes to mind. At the wake, I gave a short speech and said that while everyone outside was celebrating the public man—the creator of literary worlds and a civic leader—we were celebrating the million little anecdotes that gave us a clear idea of who he truly was, what moved him, what saddened or outraged him. I shared a story from when I was eight: one night we thought burglars were trying to break into the house, and he grabbed a slipper and went out to confront them. Halfway there he realized how absurd it was—but he kept going, because he was a dreamer. He would throw himself into illusions, regardless of reality. Then reality would crash into him and turn everything upside down—but those are the things I remember most vividly.

And then there are the values. I became politically conscious when my father broke with the extreme, pro-Cuban left. I saw the hate campaigns that were launched against him—it was very hard as his son. Today, things are different, but back then, in the cultural world, criticizing Cuban totalitarianism meant becoming isolated, left completely alone. I grew up watching a father stand against the whole world. That taught me that your sense of truth—what you believe to be true—must prevail over trends, convenience, or opportunism. You must be morally upright and defend your beliefs regardless of the cost. I also learned that an intellectual must constantly examine his convictions in light of reality. My father could be a dreamer in many things, but when it came to civic or political values, he was a man of great integrity. If he felt that reality proved his beliefs wrong, he would say so without fear. That’s why the volumes collecting his journalistic writings, like Against the Grain (Contra viento y marea), are so interesting: they trace a journey across nearly the entire ideological spectrum. And that journey is, in itself, an act of immense honesty—of saying, “This is how things are, and this is why I evolved.”

Alejandro: I share that sense of integrity. My father was always faithful to his convictions. He was deeply rooted in Christian values, but not in a theoretical way—he lived them through his actions. He never took advantage of situations where he could have. He was an old-fashioned gentleman. He adored my mother and placed her on a pedestal, expecting us to treat her with the same respect. He always conducted himself with great dignity. I never heard him argue or say a harsh word. As a young man, I felt very different from him, not recognized in some aspects. He didn’t understand or value poetry—he wanted me to focus on the business. And that was hard for me. One day he sat me down and said, “If you want to study philosophy or literature, that’s fine, but I’m not going to support you.” And even though I didn’t want to be submissive, I was pragmatic. I decided to learn how the company worked, devote myself to it for twenty years, and then step away from the day-to-day. During those twenty years, I was extremely successful—I multiplied the company’s value tenfold—and my father came to trust me deeply. He didn’t want me to leave. But I built a very strong team, which still runs things today. A close friend remains the group’s CEO, my siblings supported the decision, and the family is involved at the board level, while daily operations are handled by professional management. That gave me time to write, do theater, and work on film scripts.

–Álvaro, during your father’s farewell, you said you were surprised by the outpouring of affection.

Álvaro: Public expressions were to be expected, of course—but people from all over the world, whom we didn’t even know, sent deeply personal messages, sharing what my father had meant to them. I realized then that my father was a writer who had crossed borders in a very unique way. I have a brother who has worked with UNHCR for over thirty years and is now based in Syria. Back in the ’90s, he was based in Pakistan and occasionally had to cross into Afghanistan. I accompanied him three times, and on one of those trips, through translators, several Afghan leaders recognized our last name and told us they had read our father’s work. More recently, when my father became seriously ill and I had to fly to Lima, a diplomat friend based in Iran had convinced me to visit the country—the only way possible for someone like me, with diplomatic support. I was touring the ancient Persian Empire when I met a translator who had translated my father’s work into Persian. I asked how that had come to be, and he told me that, as a young man, he had read Conversation in the Cathedral, and the book helped him discover his calling: to bring Latin American literature to Iranian readers.

–Alejandro, you have a film project in the works that was inspired by a conversation with Pope Francis. What kind of relationship did you have with him?

–Very close. We used to write to each other, and I visited him several times. The first time, I brought him a poem I had written for him, A Gift for Francis. He was very moved, and that marked the beginning of our relationship. Because we shared that affinity, he would also listen to me—he was interested in how certain issues were perceived from the outside. He was an admirable person, with a great heart. Our connection was rooted in human fraternity—the belief that we are all children of God and therefore brothers and sisters. That utopia gives meaning to my life: to contribute my drop of water. I write from the belief that our differences are superficial—that we are spiritual beings with the same origin and destiny. And during our time in this world, we must try to make a difference in the lives of others, no matter how small. That’s what I’m working toward.